Jean-Philippe Haure was born in 1969 in Orléans. He currently lives in Bali – Indonesia – with his Balinese wife and two children in an artists’ village where he built his house. He graduated from the Boulle school, the Parisian establishment renowned for its high-level training in crafts such as cabinetmaking in which Jean-Philippe excels. This is how he worked on the restoration of pieces of national furniture.

I first met Jean-Philippe in the summer of 1990. He came from the Fleury Abbey in Saint-Benoît-sur Loire where he was a novice. He was preparing to leave as a volunteer for the island of Bali, and was to join Father Maurice Le Coutour … I saw him a second time the following year when, having arrived at work, he was running and developing a cabinetmaking workshop in Gianyar on the territory of the Catholic parish.

From 1996, he took over the management of the vocational school that Maurice le Coutour had founded and that he had just left to return to Cambodia. He cultivates and develops his gifts through photography, drawing and painting. He began to exhibit his work from 1997. In connection with the MEP missionaries in Indonesia, he participates in their retreat and annual meeting. He himself, on several occasions, welcomed and accompanied volunteers sent by the MEP.

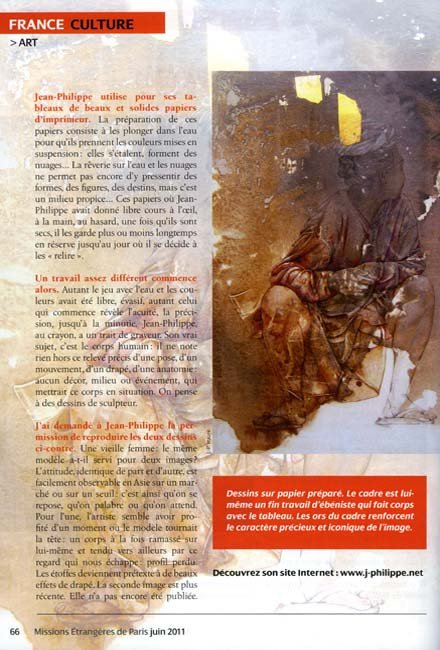

Jean-Philippe uses beautiful and solid printer’s paper for his paintings. The preparation of these papers consists of dipping them in water so that they take on the suspended colours: they spread out, form clouds… The reverie on water and clouds does not yet allow one to sense shapes, figures, destinies, but it is a favourable environment… These papers where Jean-Philippe had given free rein to the eye, to the hand, to chance, once they are dry, he keeps them more or less long in reserve until the day he decides to “reread” them.

A rather different work then begins. As much as the play with water and colours had been free, evasive, as much as the one that begins reveals the acuity, the precision, even the meticulousness. Jean-Philippe, in pencil, has an engraver’s line. His real subject is the human body: he notes nothing beyond this precise recording of a pose, a movement, a drape, an anatomy: no setting, environment or event, which would put this body in a situation. One thinks of sculptor’s drawings.

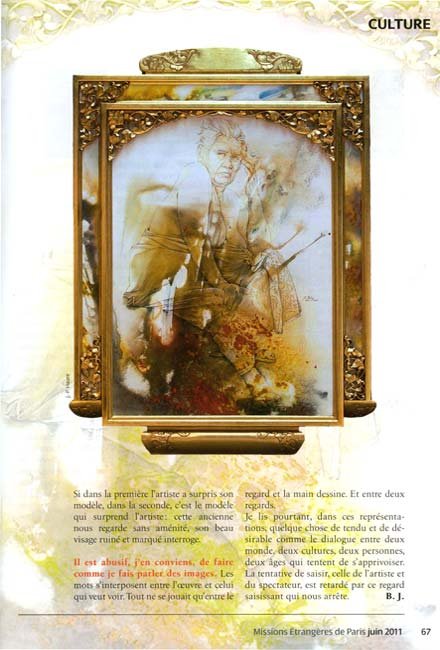

I asked Jean-Philippe for permission to reproduce the two drawings opposite (see end of article). An old woman: was the same model used for two images?

The attitude, identical on both sides, is easily observable in Asia on a market or on a threshold: this is how we rest, talk or wait. For one, the artist seems to have taken advantage of a moment when the model turned her head: a body both hunched over itself and stretched out elsewhere by this gaze that escapes us: lost profile. The fabrics become a pretext for beautiful drapery effects. The second image is more recent. It has not yet been published. If in the first the artist surprised his model, in the second, it is the model who surprises the artist: this old woman looks at us without amenity, her beautiful ruined and marked face questions.

It is abusive, I agree, to do as I do by making images speak. The words interpose themselves between the work and the one who wants to see. Everything was played out only between the gaze and the hand that draws. And between two gazes. However, I read, in these representations, something tense and desirable like the dialogue between two worlds, two cultures, two people, two ages that are trying to tame each other. The attempt to grasp, that of the artist and the spectator, is delayed by this striking gaze that stops us.

B. J.